Commitment to Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion

The mission of the Charleston Symphony is to inspire and engage our community through exceptional musical performances and education programs. The artistic vision of the CSO is to be recognized for both performance and presentation of the highest quality music, and to engage and enrich people of all ages, race, or economic status by exploring, experiencing, and creating classical music.

Even before the CSO was officially founded in 1936, the volunteer orchestra came together to serve our community. CSO members partnered with the Avery Normal School (the first secondary school for African American students) to perform a concert of unity in response to the 1919 Charleston Race Riots.

In June 2020, the CSO presented “Call and Response: A Concert for Equality” to leverage the power of music and spoken word to promote unity, love, and understanding. This concert featured the music of African American and Afro-British composers, interspersed with testimonials from community leaders. This was the first conversation of an ever-growing and expanding discussion about racial prejudice in Charleston that is filled with meaningful reflection and empathy for others. The program signified a critical launching point for our new focus on serving ALL of Charleston.

As part of the Charleston Symphony’s commitment to this work, a new ad hoc committee was launched in 2020. While the DEI committee’s mission is still evolving, the most recent version is: “Helping the Charleston Symphony embody and champion diversity, equity, and inclusion in all its endeavors.”

COMPOSERS OF COLOR

Featured for Black History Month and Women’s History Month

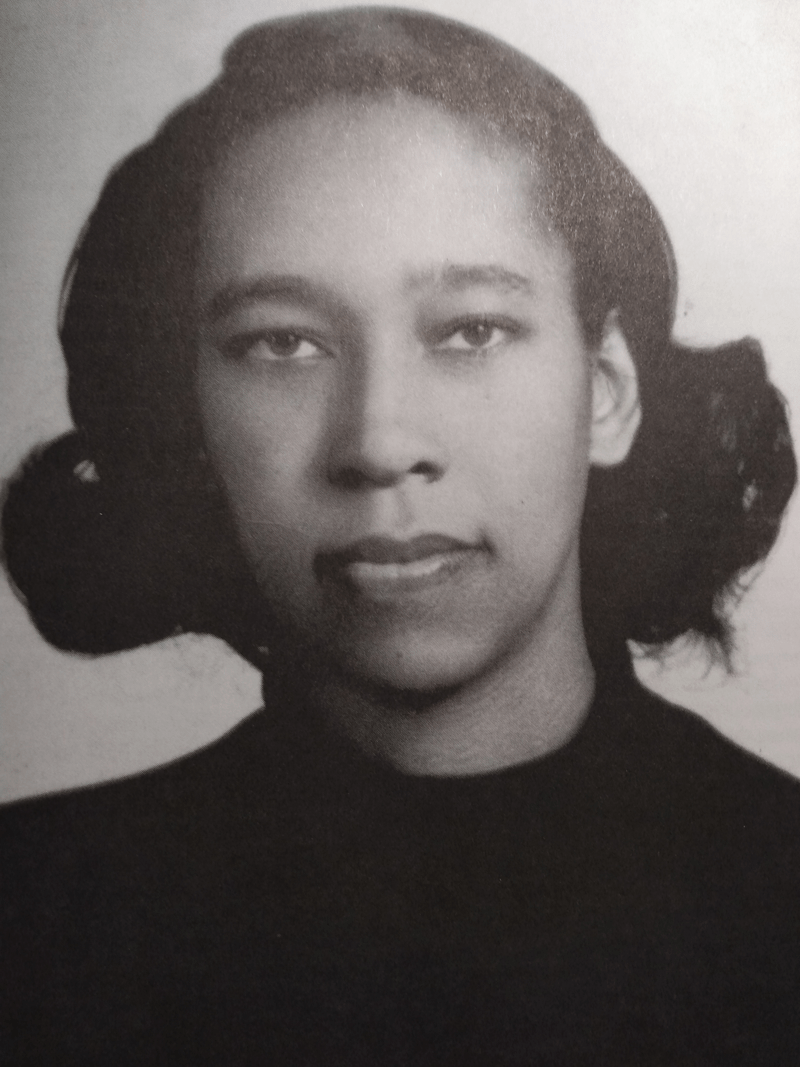

Margaret Bonds (1913-1972)

The African-American intellectual and cultural renaissances of early 20th century cities such as Harlem, Pittsburgh, Chicago, and Charleston were illuminated by many great individuals in music, dance, visual art, fashion, literature, and politics – names such as Langston Hughes, Zora Neal Hurston, Louis Armstong, Marcus Garvey, Duke Ellington, and Florence Price come to mind.

If you asked some of these visionaries to name other great contemporaries, they may mention the Chicago-born piano and composing prodigy, Margaret Bonds.

Bonds composed her first work, Marquette Street Blues at age 5. By the time she passed at age 59, she had completed nearly 100 works for solo instruments, chamber orchestra, full orchestra, solo voice, chorus, incidental music, and full orchestra with chorus and soloist, including several cantatas.

On December 11th, 1960, the full version of her Christmas cantata, The Ballad of the Brown King, the story of King Balthazar, one of the Magi witnessing the birth of Jesus who had dark skin, made its television debut sung by the Westminster Choir and orchestra on the CBS special Christmas, U.S.A. The original version of the work was finished in 1954 – Bonds composing music set to libretto written by writer and activist Langston Hughes, who also commissioned the work.

Each of the nine movements outlining the aspects of the birth of Christ are exemplary of Bonds unique compositional style, utilizing: sacred subject matter, tertian and quartal harmony, chromatic voice leading, improvisatory and conversation syncopated rhythms, and the periodic infusion of other sacred and secular music forms such as hymns, gospel, jazz, and calypso.

Other great works by Margaret Bonds are: Three Dream Portraits, Troubled Water, Spiritual Suite, and Credo.

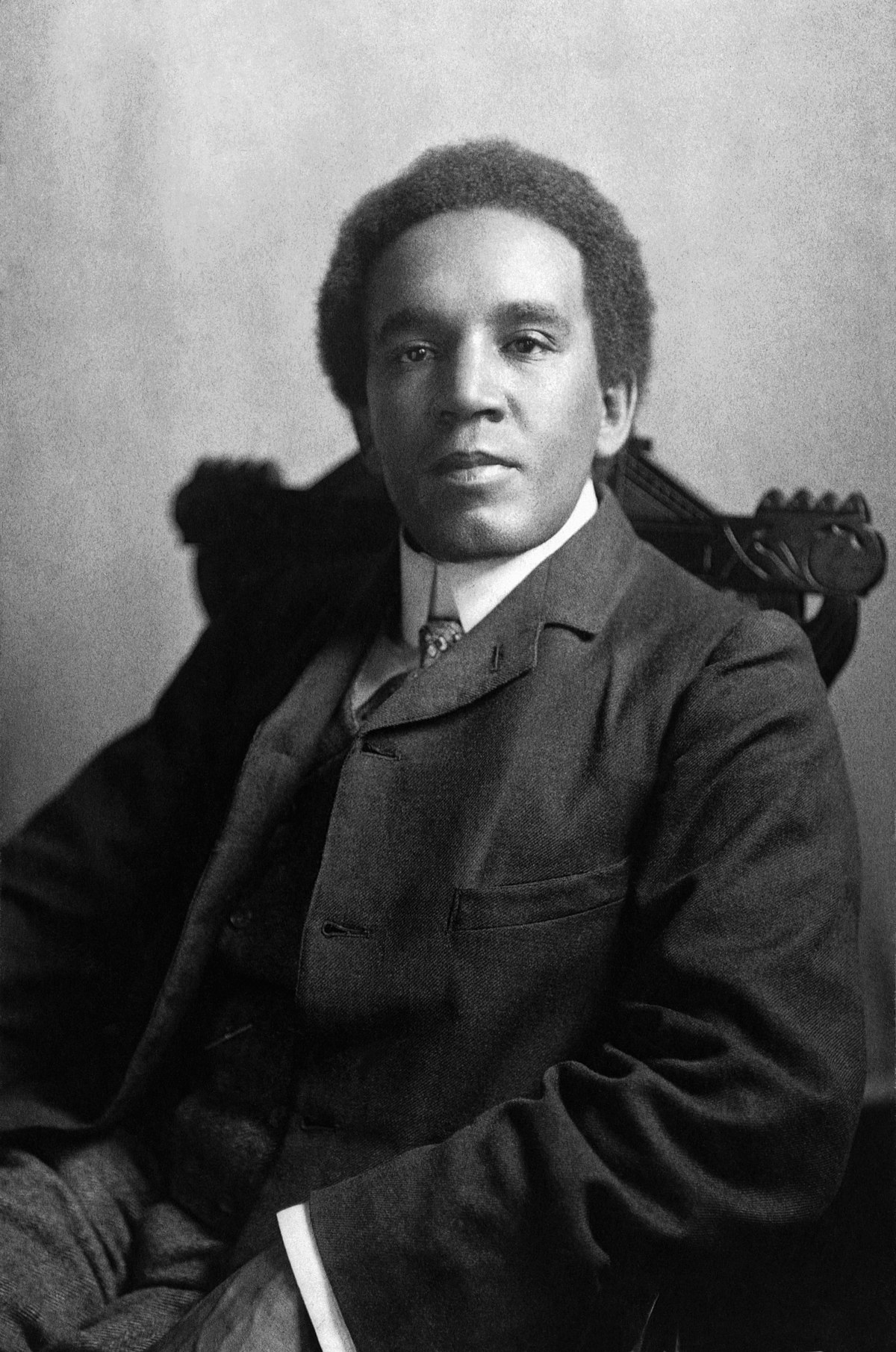

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor (1875-1912)

At the young age of 37, Afro-British composer, Samuel Coleridge-Taylor passed away due to complications related to pneumonia. He is survived by an awe-inspiringly large musical output spanning a brief compositional career, including: 39 works for solo instruments, 8 chamber works, 1 piece for string orchestra, 8 works for soloist and orchestra, 3 compositions for orchestra and chorus, 73 songs for solo voice, 41 works for chorus or vocal ensemble, 11 cantatas and operas, and 9 works of incidental music.

At 22 years old he reached international fame for his cantata for chorus, orchestra, and tenor, Hiawatha’s Wedding Feast, based on the Henry Wadsworth Longfellow epic poem, The Song of Hiawatha. In his brief lifetime, over 200,000 copies of the cantata were sold, and it rivaled Handel’s Messiah and Mendelssohn’s Elijah in frequency of performance. Unfortunately, fearing a lack of opportunities, Coleridge-Taylor sold the rights to the work shortly after its premiere.

The form of the epic cantatas follows the plot of Wadsworth’s poem and Coleridge-Taylor consistently relies on text painting to best illustrate the narrative – along the way, utilizing rhythmic patterns traditionally associated with Native American culture, and employing the luscious romantic harmonies of his day.

Other great works by Samuel Coleridge-Taylor are: Hiawatha Overture, Symphonic Variation on an African Air, Ballade in A Minor, Four Novelletten, and Petite Suite de Concert, Nonet in F Minor.

Florence Price (1887-1953)

On June 15th,1933, the Chicago Symphony and conductor, Frederick Stock performed a program celebrating The Negro in Music, with works by Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, spiritual arrangements and arias for tenor and orchestra sung by Roland Hayes, the John Alden Carpenter Concertino for Piano and Orchestra performed by Margaret Bonds, and the world premiere of Florence Price’s Symphony No. 1 in E-minor – making her the first African-American woman to have a work performed by a major orchestra.

The four-movement work was constructed with classical forms and African-American folks’ idioms as each movement’s thematic foundation, while giving stylistic nods to two other compositional greats along the way: Antonin Dvorak and Samuel Coleridge-Taylor. Additional percussion instruments evoke sounds of the New World and the African continent: cathedral chimes, large and small African drums, wind whistle, and bells.

The emotionally charged sonata form first movement, Allegro ma non troppo, has two primary themes, a reflective yet restless e-minor based 5-note pentatonic scale in the style of a spiritual(c-d-e-g-a), and a distinctly Dvorakian G-major subject that echoes the second theme from the Czech nationalists’ ninth symphony’s opening movement.

The second movement, Largo maestoso, reflects musical style and vernacular intimately familiar in African-American congregations – starting with a 28 bar call and response between a solemn brass hymn-style chorale over syncopated timpani and African drum pulse spelled with pacifying flute and clarinet interludes.

The third movement, Juba Dance, is a light-hearted syncopated antebellum folk dance reminiscent of a fiddler’s rhythm over off-beat bass. The Finale presto is a dauntless yet graceful rondo based on an ever-present four bar triplet motive.In recent years, the music of Florence has become resurgent. Other great works by this 20th century revolutionary are Ethiopia’s Shadow in America, Symphony No. 3 in C-minor, and Piano Concerto in One Movement.

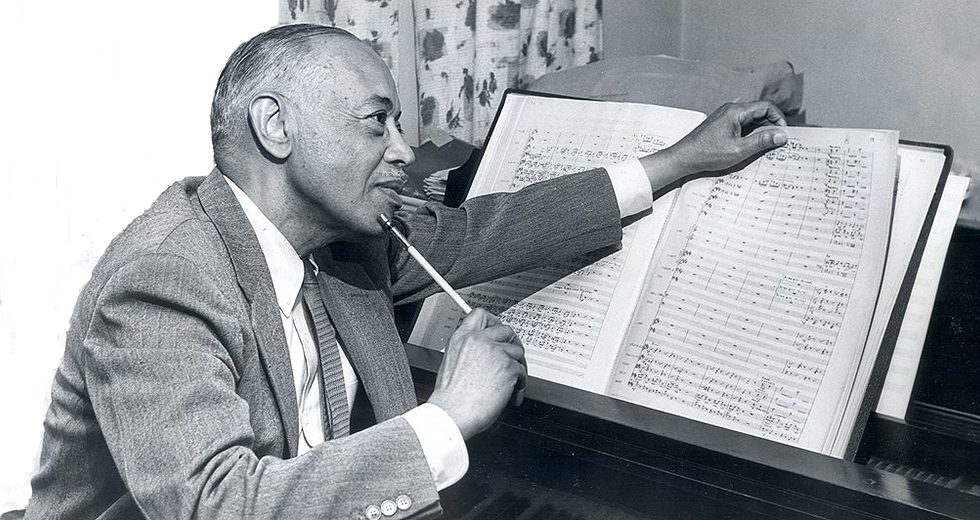

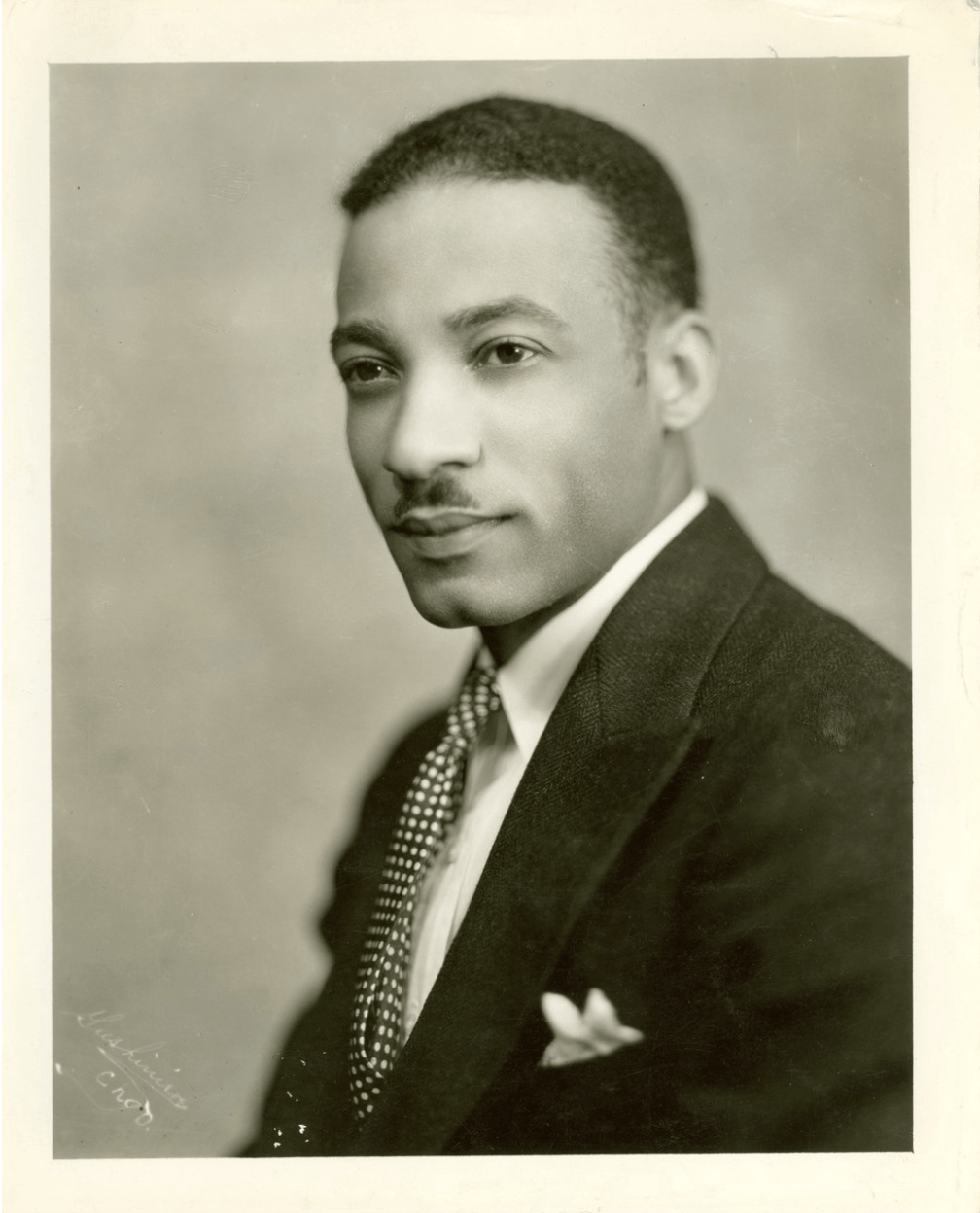

William Grant Still (1895-1978)

Few composers were as prolific as William Grant Still – writing over 200 works for solo instrument, small chamber ensemble, chamber orchestra, full orchestra, wind band, solo voice, chorus, ballet, cantatas, and operas.

His 1930 Symphony No. 1 in A-flat was the first complete symphony composed by an African-American; and its premiere by the Rochester Philharmonic was the first to be performed by a major symphony.

The four-movement work is an elegiac journey born out of the Harlem Renaissance’s celebration of black culture and art. Each movement is ascribed a subtitle from a Paul Laurence Dunbar dialect poem – Longing, Sorrow, Humor, and Aspiration – each exploring the emotions of the pre-Civil War enslaved black Americans.

The first movement, Moderato assai – Longing, is constructed on a hybrid foundation of both American blues and European classical conventions. It’s first theme is a 12-bar blues, from which all the following movements borrow material.

The final movement, Lento, con risoluzione – Aspirations, is a deeply moving, haunting, and hopeful emotional journey that ultimately culminates in adamant resolve and strength of the people for whom he wrote it, the Sons of the Soil.

The Mississippi native, is an Eastman School of Music graduate, a Guggenheim fellow, composition pupil of Edgard Varese and George Whitfield Chadwich, and upon his Los Angeles Philharmonic debut, was the first African-American to conduct a major US orchestra.

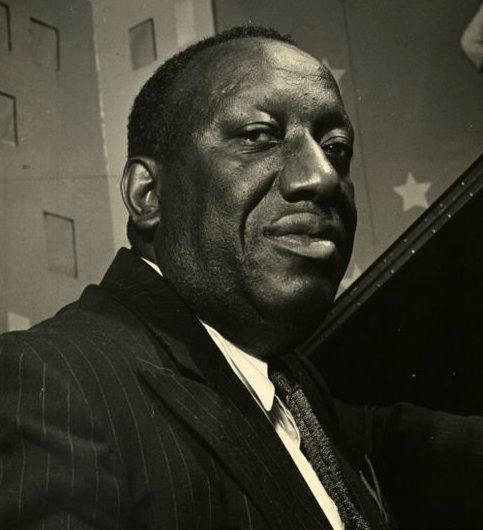

James P. Johnson (1894-1955)

You may know James P. Johnson as composer of The Charleston, a number from his 1923 Broadway musical, Running’ Wild; but what if I told you the New Brunswick, NJ native wrote dozens of solo piano stride and classical works, a string quartet, twelve full orchestra compositions, over two-hundred songs, and twenty-five stage productions, including musicals and ballets…

The score for Johnson’s Harlem Symphony was considered lost until the late 1980s when discovered among his personal papers in a family archive.

The 1932 symphony is four movements of reflections and scenes of New York life: Subway Journey, April in Harlem, Night Club, and Baptist Mission.

Subway Journey is a raucous and gleeful musical tour from Penn Station with stops along 110th Street – the Jewish Neighborhood, 116th Street – Spanish Neighborhood, 125th Street – the Shopping District, and 135th Street – the Negro Neighborhood. The orchestra depicts the soundscape of street cars, automobile horns, horse hooves, and shuffling pedestrians, all on a foundation ragtime rhythm.

April in Harlem is a slow, nostalgic, and affectionate love song full of luscious chromatic melodies over rich harmonies that could only come from a pen that also wrote for television and the Hollywood big-screen. Lyrical clarinet, horn, and trombone solos spelled by ever churning and rising passionate string interjections.

Night Club constantly developing and varying sixteen bar rag depicting the nightlife of a Hell’s Kitchen basement club. The first theme is based on the work of his mentor, Charles Luckeyeth “Luckey” Roberts; and the second is a twist on Johnson’s own work, Twilight Rag.

Baptist Mission is a dramatic and moving seven-variation passacaglia on a syncopated version of the hymn, I Want Jesus to Walk with Me.

Johnson is most remembered as the father of stride piano and a major influence on jazz greats such as Count Basie, Duke Ellington, Art Tatum, and Fats Waller, but Johnson believed that jazz could be the foundation of American classical music via the symphonic medium.

Coleridge-Taylor Perkinson (1932-2004)

Coleridge-Taylor Perkinson’s 1956 work, Grass: A Poem for Piano, Strings, and Percussion was the American composer’s rhapsodic response to the tragedy and brutality of the Korean War and was inspired by the Carl Sandburg poem sharing the same name. This conversation between piano and accompanying ensemble speaks from the perspective of grass, gradually covering the signs of barbarism and the fallen who sacrificed themselves for others.

Perkinson has a voice all his own. Other twentieth century composers brought the aesthetic of jazz to the symphonic stage, but none have found a way to seamlessly weave blues, jazz, spirituals, with baroque and romantic form and style.

The New York City native wrote works for solo instrument, voice, chamber ensembles, string orchestra, chorus, jazz ensemble, ballet, and television & commercial incidental music for the ABC network.

Other hallmark works by Perkinson are Louisiana Blues Strut, Black Folk Song Suite for Cello, and String Quartet No. 1 “Calvary.”

Jessie Montgomery (1981-present)

Jessie Montgomery’s three-minute fanfare, Starburst, is a firework display of vivid technicolor sonorities and constant dialogue between rapidly explosive motifs and gently streaming composite melodies. This is a piece that truly showcases the full capability of a string section. In recent seasons, it has been performed by the Minnesota Orchestra, San Francisco Symphony, Los Angeles Philharmonic, The Boulder Philharmonic, Hilton Head Symphony, Detroit Symphony, Charlotte Symphony, Cincinnati Symphony, and many others.

Montgomery wrote the piece in 2013 for the Sphinx Virtuosi, a conductor-less 18-member elite string ensemble of Black and Latinx musicians during their yearly tour. Montgomery, also a violinist, performed in the ensemble.

Starburst is available in string orchestra and chamber orchestra contingents. Find more of her work at www.jessiemontgomery.com.

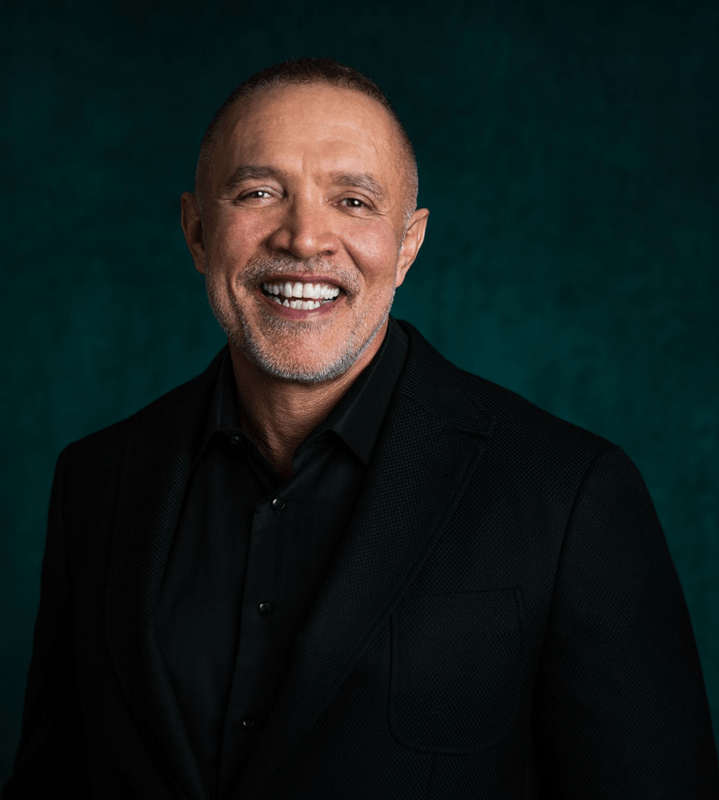

Michael Abels (1962-present)

Did you see the 2017 Oscar-winning film, Get Out? Or the 2019, thriller, Us? How about Bad Education or See You Yesterday? Did you love the soundtracks? If so, you will be pleased to meet composer Michael Abels, the man behind the music.

The Phoenix, Arizona native is most commonly known for his film scores, but his broader output consists of works for orchestra, voice, piano, opera and chamber music. His works have been performed by the Chicago Symphony, the Cleveland Orchestra, the Atlanta Symphony, the Philadelphia Orchestra, Chicago Sinfonietta, and many more. As a conductor, Abels has led the National Symphony and the San Francisco Symphony in special performances of Get Out: In Concert.

Abels is a co-founder of the Composer Diversity Collective, an advocacy group to increase the visibility of composers of color. Find more of Micheal Abels music and projects at michaelabels.com.

Julia Perry (1924-1979)

The Lexington, Kentucky native, Julia Perry composed the majority of her work between the 1940s and late 1960s. Perry created works for nearly every genre, including piano, voice, chamber music, choral, opera, ballet, and orchestra – she even composed ten symphonies!

At a time when some of the most well-known American composers such as Aaron Copland, George Gershwin, and David Diamond were at the height of their powers, Julia Perry earned critical acclaim and numerous prestigious awards, such as:

- National Association of Negro Musicians, Voice & Composition Competition (1948)

- Boulanger Grand Prix (1952)

- Guggenheim Fellowship (1954 & 1956)

- National Institute of Arts of Letters Award (1964)

- Honorable Mention, ASCAP Award to Women Composers for Symphonic & Concert Music (1969)

Unfortunately, her ability to sustain a public life in music was shortened by paralytic effects after suffering a massive stroke. Without question, the marginalization she suffered as an African-American, a woman, and a person with a disability in the early-twentieth century led to her magnificent work being largely neglected and omitted from American classical music canon.

Her 1952 Short Piece for Orchestra was premiered by the Turin Symphony (Italy) under the direction of Dean Dixon, an African-American expat conductor whose career rose to prominence in Europe.

A 1965 performance by the New York Philharmonic and William Steinberg brought national attention to the work. This was only the third composition written by a woman performed by the Philharmonic, and the first ever written by a woman of color.

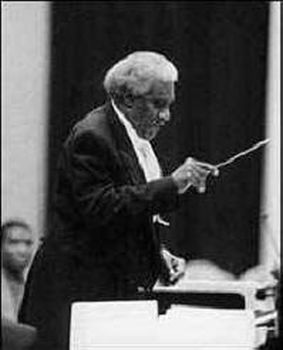

William L. Dawson (1899-1990)

November 20, 1934 was the first of four consecutive nights that 35-year-old composer William Dawson received lengthy, thunderous standing ovations at Carnegie Hall for his new work, Negro Folk Symphony. Led by Leopold Stokowski, the Philadelphia Orchestra introduced the public to Dawson’s three-movement work that became an audience favorite.

A national CBS radio broadcast during its premiere week and numerous performances over the next 18 months made Dawson’s work an immediate success. An early New York Times review referred to his symphony as, “the most distinctive and promising American symphonic proclamation which has so far been achieved.”

The Anniston, AL native held musical degrees and training from the Tuskegee Institute (AL), Washburn College (Topeka, KS), American Conservatory of Music (Chicago, IL), Chicago Musical College, and the Eastman School of Music (Rochester, NY).

Before his composing career, he was principal trombonist of the Chicago Civic Orchestra (1926-30), and conductor of the Tuskegee Choir (1932) for the opening Radio City Music Hall and performances at the White House for Presidents Hoover and F.D Roosevelt.

Dawson passed on May 2, 1990 in Montgomery, AL, but leaves behind a tapestry of symphonic works, chamber music, choral works, and songs for solo voice. Listen to Dawson’s passionate and deeply moving Negro Folk Symphony, performed by the Detroit Symphony Orchestra conducted by Neeme Järvi via the link, here.

Coming soon…

- Edmund Thornton Jenkins

- Trevor Weston

- Scott Joplin

- Ulysses Kay

- and more